This November, fishers from the Maldives will begin catching gulper sharks. Meanwhile, 4,000 kilometres away in landlocked Samarkand, Uzbekistan, nations are preparing to vote on bolstering protections for these very animals.

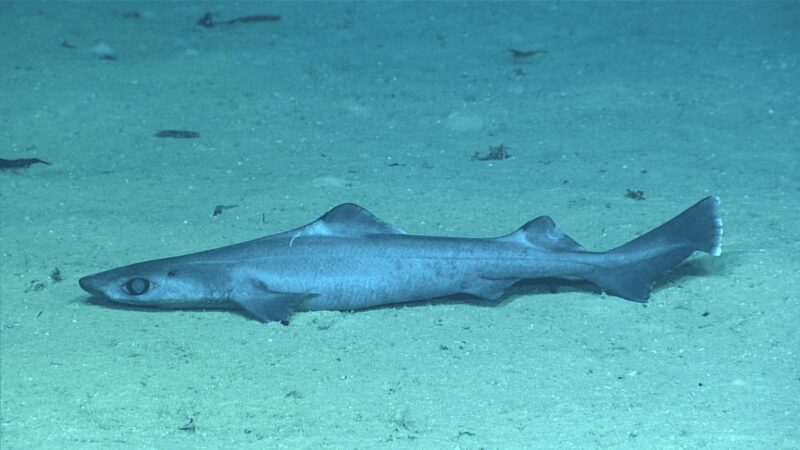

The Maldivian president Mohamed Muizzu announced in August that his country will once again begin fishing for gulper sharks, a deepwater species targeted for its oil which is used in health supplements.

Gulper sharks are extremely vulnerable to overfishing. Populations are estimated to have collapsed by 97% in the Maldives and more than 80% globally. Several species are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Since banning shark fishing in 2010, the Maldives has been seen as a haven for the species. Conservationists have described any resumption as a potential tragedy.

Illustrating the ongoing tension between conservation and economics, Muizzu insists fishing would take place with a “comprehensive management plan”. He adds shark fishing has been a “significant source of income” for his country in the past.

The Samarkand vote on restricting international gulper shark trading will happen at the two-week conference of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which starts on 24 November. In total, 71 species of sharks and rays have been earmarked for greater protections.

The vote is being led by the United Kingdom, which did not stop the Maldives unveiling its new fishery brand, “From Maldives”, there in July.

Sharks in crisis

Global shark populations collapsed by 71% between 1970 and 2018, according to a scientific study published by Nature in 2021. The results identified overfishing as the primary cause. Glenn Sant, fisheries expert at Traffic, a wildlife trade NGO, says this drastic reduction in sharks is likely to be having a “huge” impact on the environment. “We need to act quite quickly,” he adds.

Sharks are often targeted for their fins, which are consumed in parts of Asia in soups and sauces. But shark meat is becoming increasingly sought after as decades of overfishing takes its toll on stocks of other fish. The trade has surged in recent years.

Gulper shark oil is prized by the cosmetics and wellness sectors. Supplements made from “shark liver oil” are commonly sold, including in the United Kingdom and Europe. Sant says species-specific export data is patchy but it is likely that a significant proportion of shark liver oil traded globally last year was from gulpers.

Sharks are also frequently taken as bycatch, meaning caught accidentally rather than specifically targeted. Once taken from the ocean in this way, they are sometimes kept and processed for commercial gain. Sant believes bycatch is no excuse for countries not to address the problem. “It allows some countries to think they don’t have responsibility to manage them,” he says. “They do have a responsibility, particularly when it’s a CITES-listed species.”

A tale of two CITES

CITES was established in 1975 but has only fairly recently shifted its attention towards marine species. The consensus had been that regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs) were better placed to regulate the fish trade.

As it became clear how many fish stocks were in trouble, however, conservationists argued more needed to be done. Emphasis is beginning to shift from bodies that manage fisheries to those that manage conservation.

“Fisheries management has been failing across the world. It needed to be treated as a conservation issue,” says Matt Collis, senior policy director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, a conservation NGO.

Shark advocates also worry the species were being ignored by RFMOs. Mark Bond, a marine reserves researcher at Florida International University in the United States, says: “If you look at their logos, none have anything but a tuna or a swordfish. Sharks are bycatch to them: they’re a pain, not the focus of management.”

Fishing fleets have been making money from sharks, Bond adds, “but they don’t want to manage them because it’s too much effort”.

The listing process

Species can be listed on one of two CITES appendices if countries that are party to the convention approve. Appendix one restricts trade entirely, while species on appendix two can be traded with a permit. Gulper sharks are proposed for inclusion on appendix two. Dialogue Earth asked the Maldivian government for its stance regarding the listing of gulpers but it did not respond.

The first sharks were listed on CITES in 2003. Inclusion accelerated in 2013 and now more than 100 species are listed.

This did not happen unopposed. Integrating Wildlife, Markets and Conservation, an NGO dedicated to “the sustainable use of wildlife”, argued in 2013 that international trade in marine species is “not well suited” to CITES enforcement measures. It says shark listings would “add an unnecessary layer of complexity” to fisheries management.

The listing of marine species by CITES continues to attract intense lobbying from many different NGOs, fishers groups and industry associations. Not least because of the amount of money involved. “We’re talking about multi-billion-dollar industries,” Collis points out. Countries with a strong commercial interest in fishing tend to use particularly loud voices. When a proposal to list bluefin tuna was made in 2010, Japan’s successful lobbying against it “was like nothing you’ve ever seen”, he says.

CITES rules dictate a species listing must gain two-thirds of the vote to be approved, with every country getting one vote. Countries with a direct stake in the trade of certain species can easily be outvoted by countries with no interest in it, which is part of the reason why lobbying is so vociferous.

Banning trade can have an adverse effect on local and Indigenous people – local fishers, in the case of sharks and marine species. It can even damage the conservation of species, some academics argue. For example, by leading to scarcity-drive price increases that fuel animal and plant poaching, and by disincentivising local engagement in conservation projects by restricting profit from traditional harvesting.

In a paper published in April, a group of academics warned the polarisation of views between conservation and trade could undermine the success of the convention. They pointed to Japan’s withdrawal in 2019 from the International Whaling Commission amid a similar dispute. They recommended more inclusive decision-making that takes the views of Indigenous people and other locals into account, alongside what scientific evidence dictates.

Assessing success

Assessing shark populations is difficult, which makes the question of whether CITES listing has helped protect them a hard one to answer. “It’s easier to count elephants because you can just do an aerial survey, but you can’t really count sharks,” thinks Bond, the marine reserves researcher. “We don’t have an absolute number for species populations.”

There are some indications, however, that more needs to be done for sharks.

Oceanic whitetip sharks were listed on appendix two in 2013, but in 2018 the IUCN declared them to be critically endangered. A coalition including the United Kingdom has proposed moving them to appendix one this year, saying “substantial illegal trade is occurring in dried oceanic whitetip fins.” There have even been concerns that CITES listings could drive up the price of fins and create informal markets by restricting legal trade.

The coalition pushing for an appendix one listing for whitetips also say that while the species is supposed to be protected by RFMOs, there has not been “sufficient enforcement” of restrictions on its trade.

Sant accuses some countries of not taking the enforcement of shark fishing rules seriously and says they have “been able to get away with it”. A 2017 study suggested trade in some listed shark species had continued without permits.

A lack of education could also be hampering the effectiveness of the convention. A study of shark fishers in Bangladesh published in 2022 found that none were aware of CITES or the restrictions it imposed.

Only some were partially aware of national laws protecting sharks.

Other researchers have a more positive take on the convention.

Work led by Bond published earlier this year found that trade regulations have improved shark and ray management for 44 species listed between 2003 and 2019. He says it is very encouraging that half of CITES member states had changed legislation in response to listings. Especially because several countries that had “little to no” shark management in place prior to a listing now have some form of regulation.

Management of trade has greatly improved, but CITES alone is not going to solve the problem

CITES also has power itself, using it last year to recommend states restrict Ecuador from trading in some species of shark due to deficiencies in that country’s own enforcement.

Bond’s study concludes that CITES can “play a critical role in improving global shark and ray conservation” but that the severity of the current “crisis” for these species renders it insufficient for combating overfishing.

“If I compare back to the early ‘90s before CITES was involved … management of trade has greatly improved,” Sant says. “But CITES alone is not going to solve the problem.”

Conservationists hope that, whatever its flaws, the additional protection of a CITES listing will be awarded to gulper sharks in November. For the delegates, they will once again have to decide where to draw the line between protecting animals and protecting the livelihoods of those who rely on them.

Dialogue Earth has approached the CITES secretariat for comment on the issues raised in this story.