Americans are anything but proud that the United States is number one in the world when it comes to two devastating metrics: mass incarceration and mass shootings.

There is also a feeling of hopelessness that anything will change when Congress consistently refuses to take any action to address either issue.

What factors contributed to the 500% increase in incarcerated citizens—catapulting the U.S. to number one in mass incarceration?

Do we have more crime than the other countries? No, that’s not it.

Keep reading to learn more about America’s history when it comes to the incarceration of its population and the recent staggering increase in mass incarceration rates.

Incarceration rate infamy

The United States is known for its high incarceration rates, but the situation has reached staggering proportions in recent decades.

With over 2 million people behind bars, the United States boasts the highest incarceration rate in the world, a dubious distinction with serious consequences.

This alarming trend has been fueled by a significant increase in the number of individuals serving time for non-violent offenses, particularly in the wake of the War on Drugs and the implementation of harsh mandatory minimum sentences.

As a result, the United States has become a global outlier, with a prison population that far exceeds that of other developed nations, even those with comparable crime rates.

Impact of rising incarceration rates

The United States locks up more people than almost any other country in the world. Over the past few decades, the prison population has exploded. And the effects don’t stop at prison walls.

Families are torn apart. Children grow up without parents. Communities lose workers, caregivers, and neighbors. Mass incarceration has reshaped entire neighborhoods — especially low-income communities and communities of color.

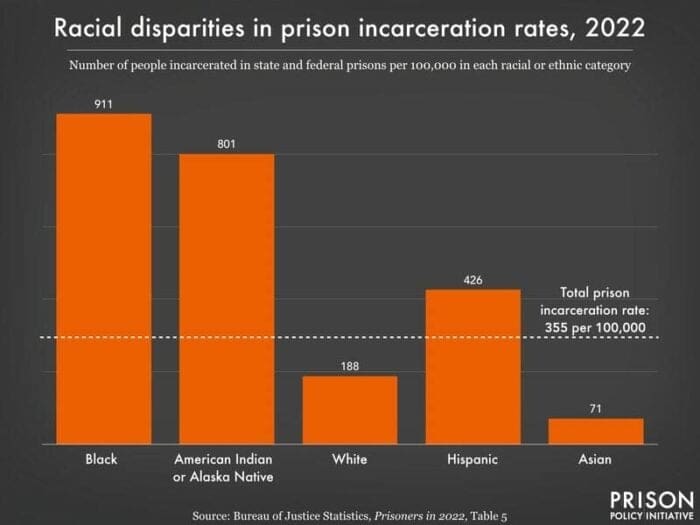

The system does not impact everyone equally. Black and Latino Americans are arrested, charged, and sentenced at much higher rates than white Americans, even when accused of similar crimes. That reality has forced many people to confront a hard truth: the criminal justice system reflects deeper racial and economic inequalities in America.

There is also a massive financial cost. The United States spends billions of dollars every year to operate jails and prisons. That’s money that could go toward schools, mental health services, addiction treatment, housing, or healthcare. Instead, it funds one of the largest prison systems in the world.

So how did we get here?

What Drove the Rise in Incarceration?

There isn’t just one cause. But two major drivers stand out: the War on Drugs and mandatory minimum sentencing laws.

The War on Drugs began in the 1970s and intensified in the 1980s and 1990s. Leaders promised to get tough on crime. Law enforcement cracked down hard on drug offenses. Penalties became more severe.

But the results were uneven.

Drug use rates were similar across racial groups. Yet arrests and prison sentences were not. Police heavily targeted certain neighborhoods. Prosecutors pursued harsh charges. Judges were often required by law to impose strict sentences, even for non-violent offenses.

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws played a huge role. These laws required judges to hand down fixed prison terms for certain crimes, especially drug offenses. Judges couldn’t consider individual circumstances. If someone was convicted, the sentence was automatic.

That meant people — often first-time offenders — were sent to prison for years for non-violent drug crimes. In many cases, addiction was treated as a criminal issue rather than a public health issue.

The result? A dramatic surge in the prison population.

The staggering increase in incarceration rates has had a profound impact on American society, with consequences that extend beyond the walls of the prison system.

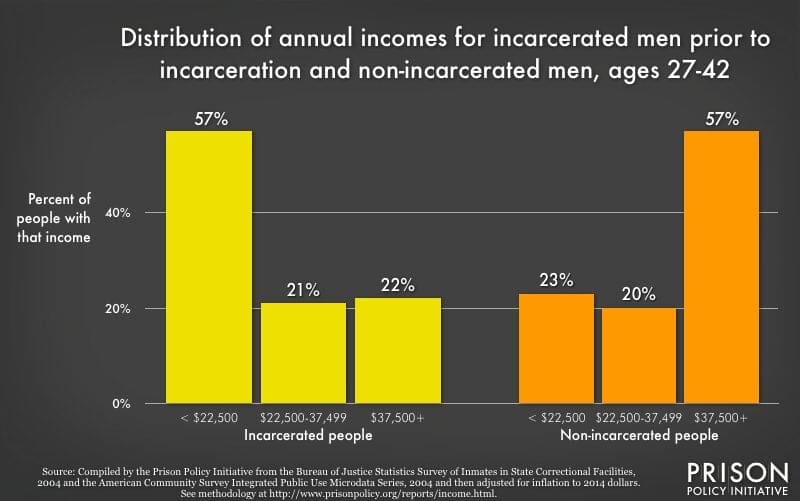

The War on Drugs wasn’t the only force driving mass incarceration. Poverty played a major role too.

People who grow up in underfunded neighborhoods often face fewer opportunities from the start. Schools are under-resourced. Jobs are scarce. Access to healthcare — especially mental health care — is limited.

When someone is struggling to pay rent, feed their family, or cope with untreated trauma, the risk of entering the criminal justice system increases. That doesn’t excuse crime. But it helps explain it.

Many people in jail are there because of circumstances tied to poverty — unpaid fines, probation violations, low-level offenses, or crimes connected to addiction. In fact, a large percentage of people in U.S. jails have mental health conditions or substance use disorders. Instead of receiving treatment, they often receive jail time.

When we ignore these root causes, the cycle continues.

Someone who is arrested may lose their job.

Without a job, they may lose housing.

With a criminal record, finding new work becomes harder.

That instability increases the chances of being re-arrested.

This cycle hits hardest in marginalized communities that were already facing economic inequality. Over time, entire neighborhoods become trapped in a system that punishes poverty instead of solving it.

The result is what many experts call a “perfect storm.”

Harsh sentencing laws send people to prison for long periods of time. At the same time, the country invests far less in education, addiction treatment, job programs, and mental health care — the very things that help prevent crime in the first place.

The system focuses heavily on punishment. It focuses far less on rehabilitation.

And that raises an important question: If the goal is public safety, is this approach actually working?

More and more people across the political spectrum now agree that something needs to change. Addressing mass incarceration requires more than building prisons or increasing penalties. It requires confronting poverty, expanding access to treatment, investing in education, and creating real pathways for people to rebuild their lives.

Without that shift, the cycle continues.

Who Is Most Affected?

Mass incarceration does not impact everyone the same way.

Black and Latino Americans are dramatically overrepresented in the U.S. prison system. Black Americans make up about 13% of the U.S. population, but they account for a much larger share of the prison population. Latino communities are also incarcerated at higher rates than white Americans.

This gap isn’t accidental. It reflects deeper inequalities — in policing, sentencing, access to quality legal defense, housing, education, and economic opportunity.

But the damage doesn’t stop with the person who is arrested.

When someone goes to prison, their family feels it immediately. A parent disappears from the household. Income drops. Bills pile up. Emotional trauma sets in.

Children of incarcerated parents are more likely to struggle in school. They are more likely to experience poverty. They are more likely to face stigma and isolation. Some research shows they are also at higher risk of future involvement in the criminal justice system.

That’s how the cycle continues — not because of personal failure, but because entire communities are destabilized.

In some neighborhoods, incarceration has become so common that it reshapes daily life. Employers are hesitant to hire people with records. Families rely on grandparents to raise children. Trust between residents and law enforcement erodes.

Mass incarceration doesn’t just punish individuals. It weakens the social and economic foundation of entire communities.

And when communities are weakened, opportunity shrinks. Stability disappears. Generational wealth becomes harder to build.

The effects ripple outward for years — sometimes decades.

The Financial Cost of Mass Incarceration

Mass incarceration doesn’t just reshape communities. It drains the economy.

The United States spends about $81 billion every year to run its jail and prison system. That money covers everything from building and maintaining facilities to paying guards, administrators, and healthcare staff.

It’s an enormous price tag.

Taxpayer dollars go toward keeping people locked up — but far less money goes toward helping them succeed once they’re released. Job training programs are limited. Mental health treatment is underfunded. Reentry support is often minimal.

When people leave prison without support, many struggle to find stable work or housing. A criminal record can shut doors quickly. Without income or opportunity, some end up back in the system.

That revolving door costs even more money.

And the financial impact doesn’t stop with prison budgets.

When someone is incarcerated, they are removed from the workforce. That means lost wages, lost productivity, and lost tax revenue. Families often lose a primary earner. Bills still need to be paid. Rent is still due.

Some households fall into poverty. Others rely more heavily on public assistance to survive.

Children may need additional services. Communities lose economic stability. Local businesses lose customers and workers.

Over time, those indirect costs add up.

There are also long-term consequences. People with criminal records often earn less over their lifetimes. They face higher unemployment rates. That reduced earning power affects their families and limits generational wealth.

In other words, mass incarceration doesn’t just cost billions in prison budgets. It quietly costs billions more in lost opportunity.

And that raises a serious question:

If we are spending $81 billion a year on incarceration, what would happen if even a fraction of that money were invested in prevention — in education, mental health care, addiction treatment, housing, and job programs?

Would we see safer communities?

The Revolving Door: Why So Many People Return to Prison

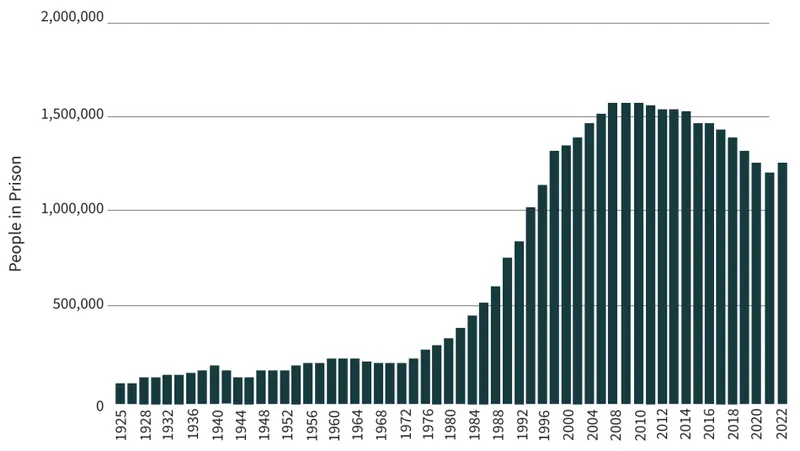

The prison population didn’t just grow — it skyrocketed.

In 1970, about 357,000 people were incarcerated in the United States.

By 1990, that number had jumped to over 1.1 million.

By 2010, it had climbed past 2.2 million.

The incarceration rate per 100,000 people more than quadrupled between 1970 and 2000.

But the story doesn’t end with how many people go to prison.

It’s also about how many come back.

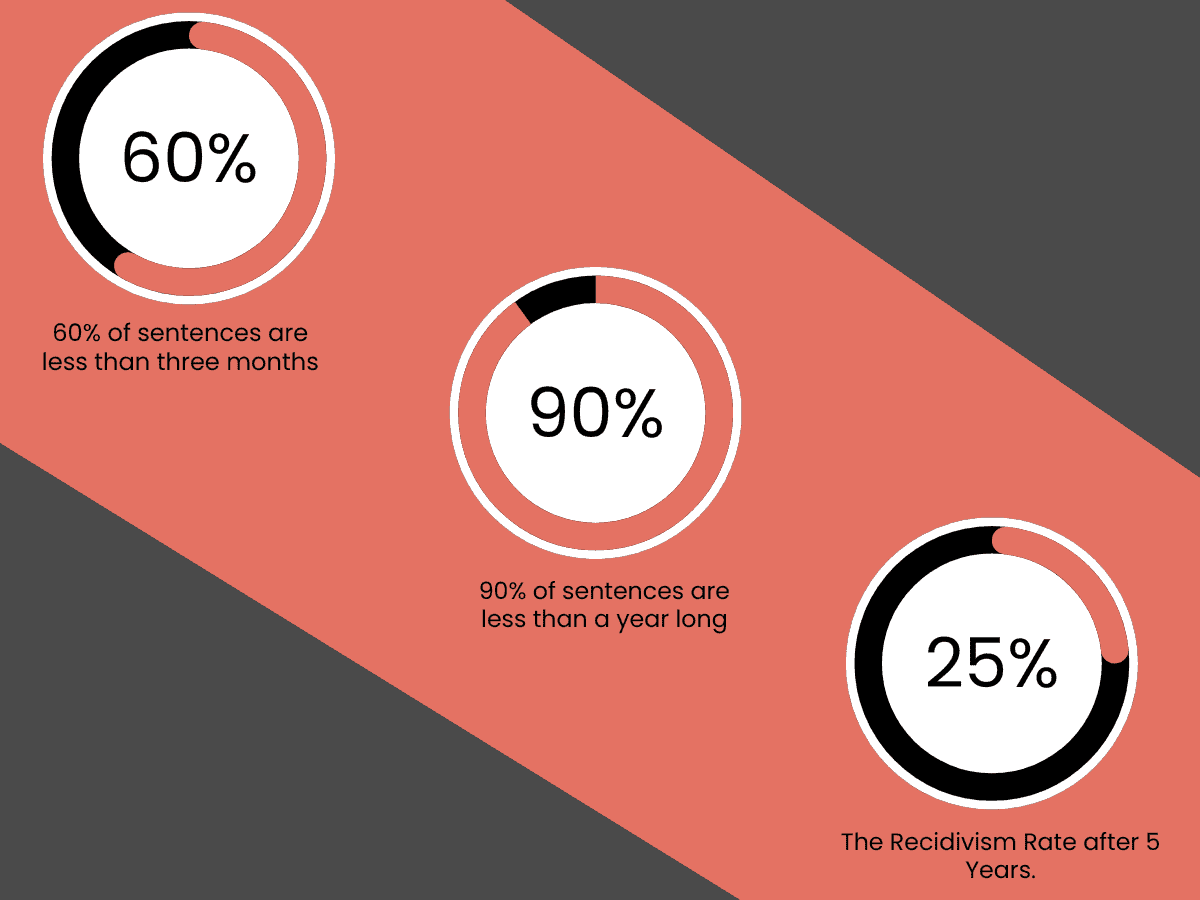

Recidivism — the rate at which people return to prison after being released — remains high in the United States. A large percentage of formerly incarcerated people are rearrested within a few years of release.

That revolving door tells us something important: the system isn’t solving the problem.

Despite the billions spent on prisons, many facilities provide limited mental health care, little meaningful job training, and few educational opportunities. People often leave prison with the same untreated trauma, addiction, or lack of job skills they had when they entered.

And once they’re out, the barriers stack up quickly.

It’s harder to find a job with a criminal record.

Housing applications are denied.

Professional licenses may be restricted.

Without stable work or housing, the risk of reoffending increases.

When rehabilitation is weak and reentry support is minimal, the cycle continues. That cycle keeps prisons full — including private prisons that depend on high occupancy to remain profitable.

If public safety is the goal, then punishment alone clearly isn’t enough.

Prison should not only hold people accountable. It should prepare them to return to society successfully.

That means access to:

– Mental health treatment

– Addiction recovery programs

– GED and college courses

– Job training and certification programs

It also means strong reentry support — help finding employment, housing, and community connections after release.

Countries that prioritize rehabilitation show a different path.

Success of Norway’s Prison System

In Norway, prisons look very different from those in the United States. The focus is not humiliation or harsh punishment. It is accountability combined with preparation.

People are treated with dignity. They receive education and job training. The goal is clear: return them to society better equipped than when they entered.

Norway’s recidivism rate is significantly lower than that of the United States.

The philosophy is simple: the punishment is the loss of freedom — not the loss of humanity.

In the United States, prison conditions often emphasize control and punishment above all else. That approach may satisfy a desire to be “tough on crime,” but it does little to reduce crime long-term.

If we truly care about lowering crime rates, the evidence points toward rehabilitation, not just incarceration.

Investing in people’s ability to rebuild their lives is not soft on crime. It is smart on crime.