First there were the catastrophic fires in Los Angeles, Latin America was overwhelmed with wildfires burning their National Forests in 2025.

In 2026, the fires in Argentina can be seen from space.

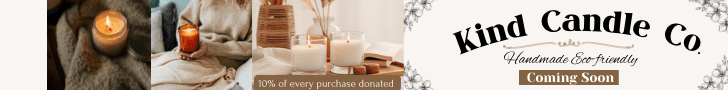

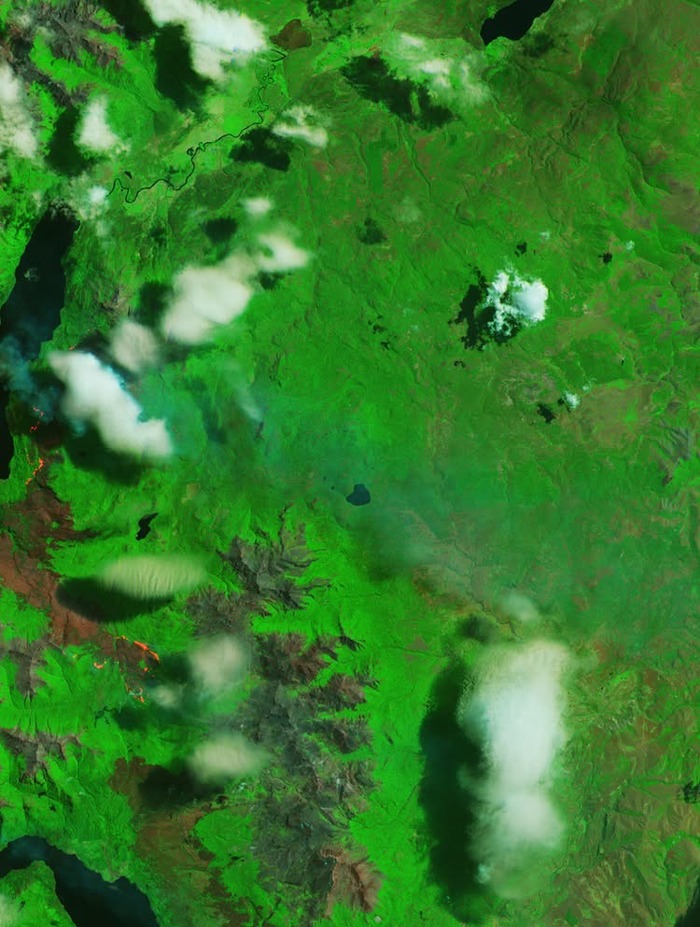

The European Space Agency posted images of the fires in Argentina (as seen from one of their satellites in space) on its Threads account.

“Patagonia is burning – and we can see it from space 🔥Captured on 11 January 2026, this image shows an active wildfire near Lake Rivadavia in Los Alerces National Park, Argentina. Home to ancient Alerce trees – some over 3,600 years old – this ecosystem is under serious threat. Shown in false colour, burned areas appear brown, the active fire front red and orange, and snow-covered regions light blue. From orbit, satellites help track fires in near real time to support response on the ground.”

As Los Angeles faced unprecedented fires razing entire neighborhoods in late January, Latin America was not spared either. In 2025, Argentinian Patagonia fires destroyed more than 10,100 hectares (24,958 acres) since summer began in the Southern Hemisphere. These fires affected Nahuel Huapi National Park, among other areas. In Chile, the forest fires by the Summer of 2025 had killed three firefighters.

In less than a month, the fires in Los Angeles, since they began Jan. 7, destroyed 18,000 homes and structures and killed at least 29 people. Those were not the first large-scale wildfires to occur in this region of the U.S. What set them apart, though, was the fact that they switched from forest fires to urban fires. A similar event occurred in Chile in 2024.

Firefighters battling the Palisades fire in Los Angeles described the combination of high wind gusts and flames as “tornados of fire.” The high winds caused structures to burn faster and the flames spread more quickly than they would in normal conditions. Fires would pop up miles away due to embers traveling in the wind.

A fire science researcher was quoted in a BBC article about LA firefighters dealing with 100mph winds and the embers they carry called “firebrands,” “There’s reports of tens of kilometres that these things have travelled, and they will land in crevices around a house, maybe some ornamental vegetation, and they will start burning the houses.”

Tornados of fire or “Firenados” Sky News spotted during the LA fires.

“The fire has finally crossed Route 40,” reports Manuel Jaramillo, director general of the Wildlife Foundation of Argentina. He is referring to the relentless fire that has been advancing since January 5th through the forests and towns of Chubut province in Patagonia, where once again, for another year, wildfires are showing no signs of letting up .

“This is the worst environmental tragedy in 20 years,” declared Abel Nievas, Secretary of Forests for the province of Chubut, in a public statement. There are at least 3,000 evacuees , and reports indicate that more than 21,000 hectares of forests, grasslands, and plantations, as well as homes and even National Parks, have been affected. This area is equivalent in size to the City of Buenos Aires.

Jaramillo is in contact with firefighters, officials, and residents of the area and explains why this scenario repeats itself every summer. Every January seems to be worse.

“Unlike what used to happen with the weather, now the fire burns almost as much at night as during the day. At night, the temperature and wind intensity usually dropped a bit. The fire, we could say, lessened its violence, its aggression. Now, the fire continues to burn at night, there is still wind, there are still high temperatures, and this makes it very difficult to ensure control,” Jaramillo adds in an interview with Mongabay Latam . There hasn’t been significant rainfall in the area for more than a month, he states. “Temperatures are reaching 32°C and we’re just starting January.”

“That’s another issue my colleagues are also telling me about,” he says. “It’s January and we already have extreme fire conditions , like we used to have in March, after we experienced all the summer heat.”

In Argentina, Patagonia is burning, but the fires also threaten other regions. “An extreme fire risk has been declared in 16 provinces, and authorities consider the situation potentially explosive or extremely critical due to high temperatures, low humidity, strong winds, and a lack of rain,” Jaramillo states. He adds, “ Some researchers say we are in the Pyrocene epoch .”

-Because?

—We’ve seen some emblematic wildfires in recent years, and this is heavily influenced by the variables of climate change, which are becoming increasingly evident. It’s primarily related to changes in temperature and humidity, but also to an increase in fuel loads [biomass] and the continuity of these fuels. Experts talk about a fire triangle : heat, fuel, and oxygen. Heat is natural or can be supplied by humans, precisely when a fire is lit. Oxygen is always available, generally to a greater or lesser degree. When there are winds, there is obviously more oxygen, and that makes the fire spread.

Fuel is what we can best manage , but it’s precisely what we’re not managing well. The quantity and continuity of fuel (biomass) are not being controlled. This means that when a fire starts, it quickly spreads and becomes increasingly difficult to control. Fire, we could say, moves according to fuel availability and oxygen levels , which are often influenced by the wind. In Argentine Patagonia, and also in the province of Córdoba, fires reach almost explosive speeds and conditions . The fires in Argentina are, year after year, a manifestation of increasingly critical situations.

—The affected areas are even repeated…

“In 2021, we had a tragedy in this same area where this fire is occurring in the province of Chubut, which we hope will not have the same consequences. In 2021, more than 600 houses burned and more than 1,500 people were affected in the Las Golondrinas fire, which demonstrated what are known as interface fires—that is, fires that develop in transition zones between urban and rural or forested areas. When I studied forestry engineering, almost 30 years ago, interface fires were studied as a potential possibility, with examples from the United States and Spain. Today, they are occurring in Argentina.”

—What are the characteristics of interface fires?

“It becomes much more complicated because what’s burning has different characteristics. It’s much more explosive, there’s a much greater risk of injury to people , there’s electricity in some cases, and there’s gas. There’s a greater risk of loss of life, of people being affected. So, forest firefighterswho are trained to work on a fire line, generally in isolated rural environments, need to have the equipment to help with structure fires. There, they collaborate extensively with local firefighters, who are often overwhelmed. It’s like multiple house fires happening all at once. I was discussing this with some of the firefighters recently.”

—What do you see when you visit and talk to the rescuers?

“A typical fire puts them under significant stress, but, for example, finding so many injured people, burned animals, is something local firefighters are sometimes not even emotionally prepared for. So, these fires have a complexity that requires greater preparation , more resources, and greater attention to the firefighters themselves, who are the heroes in these situations.”

We must consider the safety of people, of the firefighters. Nature is important; it must be preserved. It is the source of many essential elements, but with work and effort, nature can recover, it can be restored. People’s lives cannot. It is important that everything be done ensuring the utmost care for the lives of the inhabitants, the residents, the firefighters, and the affected personnel.

—There were budget cuts by Javier Milei’s government to the area of fire prevention. What state is the country in to face these crises?

—In 2013, the Federal Fire Management System was created by law , integrating four sectors: the National Fire Management Service, the provinces, the National Parks Administration, and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. This system is collaborative and assists each provincial jurisdiction with personnel, resources, logistics, operations, and aerial support when needed and upon request.

The Federal Fire Management System administers the aerial resources , which is why the national government usually pre-contracts them, and they are largely leased because the government cannot afford to maintain an aircraft. What the National Service does is pre-contract the flight hours. If you don’t have a good contract, one that you pay well and on time, companies will lease the planes to Brazil, Paraguay, or Chile, and you lose the opportunity to have good equipment available when a fire strikes.

Then there is a Fire Management Law of 2012, which is to prevent and combat forest fires and gives responsibility to the national authorities over the National Fire Management Service, which is now in charge of the Undersecretariat of Environment and the National Parks Administration.

The law mandates the development of fire management plans to prevent and suppress fires at the provincial, regional, and national levels, and allocates funds from the national budget for their implementation. Unfortunately, this year, in particular, our budget represents only 0.014% of the total budget for the National Fire Management System, reflecting the inadequate conditions for planning these events. It’s important to note that this is a recurring issue; the budget has never been substantial under any administration.

Despite this, over the last 30 years we could say that the entire National Fire Management System has been strengthened. There are many more firefighters, they are in better condition in many provinces, they are now permanent staff, and they have prevention or fuel control duties during the low fire season. The problem is that, when there isn’t a fire, there should be an equal or greater amount of resources dedicated to prevention.

—How should it be prevented?

—In very general terms: reduce the fuel load [biomass] and prepare response structures for when there is an emergency. And here’s the thing: fires can be prevented with controlled burns. They are essential to reduce the continuity and fuel load, perhaps not so much in forest ecosystems, where burning pruning waste can burn grasslands that create continuity, but much more so in grassland ecosystems, like in the province of Corrientes, where we had serious fires in 2022, 2023, and subsequently. Burns should be carried out under controlled conditions when the weather permits, with trained personnel, and with the necessary equipment to control any escapes from those burns.

This is crucial to prevent excessive fuel availability and ensure the fires continue uninterrupted . Therefore, it is extremely important to promote the strengthening of the National Fire Management System.

—The Wildlife Foundation is in constant dialogue with national and provincial authorities in Argentina. What responses do you receive when you raise these issues regarding fire management and wildfires?

—Since the Fire Management Law came into effect in 2012, the Foundation has had various relationships with different governments. Generally, at the political level, fire only becomes a topic of conversation once a fire has already broken out and reached such a scale that it has become a public issue. At the technical level, within government structures, there is a great deal of preparation and concern for improving both technical and political coordination.

In some cases, unfortunately, a lack of communication between some provinces and the national government, under different administrations, has either facilitated or delayed the National Service’s actions. Sometimes we try to coordinate, as when there were disagreements between the authorities during the fires in Corrientes a few years ago. It took them quite a while to reach an agreement. It’s regrettable.

Several years ago, there was talk of approximately $82 million coming from the Green Climate Fund for results-based payments related to avoided deforestation. These funds were allocated to the 24 provinces for various activities. One of these activities was precisely the development of fire management plans, which are required at the provincial level. Unfortunately, these funds have not been allocated, and those that have been allocated have not been properly implemented, according to press reports.

—What did the firefighters and their contacts tell you about the fires in Chubut?

—I was in the now-affected area in October, in Puerto Patriada, right where the fire started in early January. The Wildlife Foundation is collaborating with the German Agency for International Cooperation, the Avina Foundation, and other institutions on a restoration plan for the fires that occurred between 2011 and 2014. In the meetings in the area, what one hears is the same old story: there is a very large amount of fuel remaining.

There’s a specific issue: pine trees. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a government-backed policy of clearing native forests and planting various species of pine, spruce, fir, cypress, and exotic conifers to promote the timber industry. The same thing was happening in Chile, where they transformed native forests into pine plantations.

In Argentina, that didn’t work, partly because the climatic conditions in the area are different. Fortunately, it didn’t work because otherwise we would have far less native forest today and many more plantations of exotic pines, like in Chile. The problem that remains is enormous because those plantations were abandoned, and when they were abandoned, they weren’t thinned or pruned. Without pruning, the pines retain their branches for a long time, which act like ladders for fire. So, every time a fire arrives, it quickly reaches the treetops, as seen in the high-altitude wildfires.

Exotic pine trees are very resinous and adapted to areas where natural fires are frequent [not Patagonia]. They use fire for dispersal. The cones explode, flying ablaze and thus starting new fires. Furthermore, the seeds are so resilient that after a fire, you’re left with a pine seedbed. This becomes a huge supply of fuel that burns again frequently.

—Official statistics state that 95% of forest fires in Argentina are caused by human activity . What could be the reasons?

“They can be for different reasons. They start through carelessness, intentionally, because someone had a fight with a neighbor, or because they want to take over the land. There are many reasons why people start fires. In some cases, it’s because they want the areas burned and cleared for productive activity . As we speak, the province of Chubut has about eight active forest fires. If more work isn’t done on prevention and reducing fuel loads, this is practically unsolvable.”

There are also a lot of lightning-caused fires appearing. Thirty years ago, this didn’t happen, or if it did, it wasn’t fully documented. The climate is changing; there are more and more thunderstorms in Patagonia, something that was very uncommon before. Lightning strikes, and it generally doesn’t rain, whereas before it did. So, today, lightning strikes and starts a fire in a remote, isolated spot in the Andes Mountains. And it doesn’t rain. It’s impossible to reach it with personnel. That’s where air support is crucial.

Are airplanes essential?

“They’re important, but no forest fire will be extinguished solely with aerial resources . We have to work on the ground, controlling the fire load through continuous firefighting and trying to create sacrifice zones, safe burns. Furthermore, in Argentina, due to different regulations, and also because of costs, the fire retardant dropped from airplanes isn’t being used much.”

Editor’s note: The number of hectares destroyed by the fire was updated on Monday, January 12.

This following article was published in 2025 and provides more history of the wildfires Latin America has been dealing with leading up to the fires in Argentina that are burning today.

In 2024, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru and Argentina were affected by fires that scorched forests and victimized people, even prompting some of these governments to declare national disasters.

How prepared is the region to face fires in 2025? Current events represent a major warning that must not be ignored. This serves as a special alert for Latin American governments, which have often limited capacity, to work toward preventing fires, allocating sufficient resources to fire management strategies and taking timely action against forest fires. The effects of climate change — such as stronger winds, elevated temperatures and prolonged droughts — are combining with human actions and intentional fires, causing wildfires with catastrophic effects.

“There is an environmental transformation in which fires spread and things become more complicated now, under the effects of climate change on a global scale,” said Enrique Jardel, a Mexican fire management specialist and professor at the Department of Ecology and Natural Resources at the University of Guadalajara.

“We’ve spent half a century discussing fire management, just like we’ve been discussing urban planning, controlling the disorganized expansion of cities and actions to mitigate climate change,” Jardel said. “Now, this is a situation in which those factors are combining and we are seeing the sad and awful example of the fires in Los Angeles, which are occurring in a densely populated region that has gone through a significant landscape transformation and which, due to the characteristics of its climate and vegetation, we can say is one of the most flammable environments in the world,” Jardel added.

“Of course, this is a lesson that we must learn, because similar conditions could happen in Latin America,” he said.

Mongabay Latam talked to several specialists to explain this complex situation in Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Chile and Bolivia.

Argentina: A fragile fire management system

Since the beginning of 2025, Argentina has faced three large-scale forest fires in the Patagonian region. In the municipality of Epuyén in Chubut province, fire has consumed approximately 3,000 hectares (7,413 acres) of forests. According to reports by several Argentinian media outlets, by Jan. 20, flames had already destroyed at least 50 homes and forced more than 200 families to evacuate the far southern part of the country.

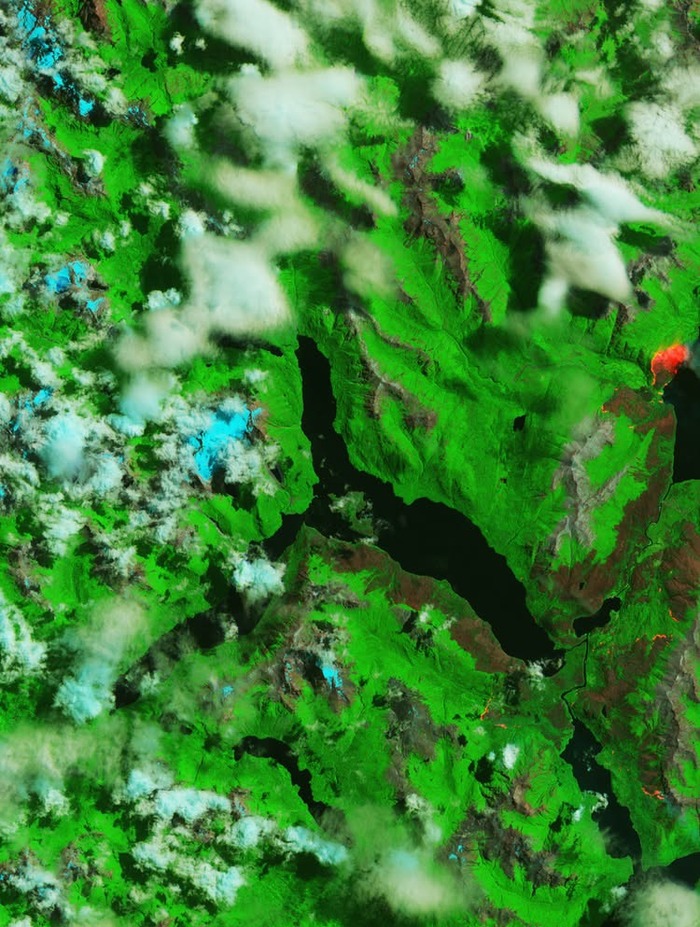

Meanwhile, another fire that began in late December 2024 in Nahuel Huapi National Park has yet to be completely extinguished. To date, it has leveled more than 5,000 hectares (12,355 acres) of this forest reserve near the border with Chile. The situation is critical: The combination of dry weather, a lack of rain, strong winds and a weak government response have complicated the outcome.

“Argentina does not seem to be prepared on a provincial or national level for a climate crisis scenario that, especially in the summertime, puts Patagonian Andean forests much more at risk,” said Hernán Giardini, the forests campaign coordinator for Greenpeace Argentina.

In late January, a third fire erupted in the area. It damaged 2,000 hectares (4,942 acres) of native forests and pastures in Chubut province, in the rural commune of Doctor Atilio Oscar Viglione, according to Giardini.

The specialist said these fires are an example of the fragility of the country’s fire management system. “On a national scale, the resources for environmental issues as a whole have been reduced. There has been a political decision to not put much money into the environment, which will have medium-term repercussions; for example, with the firefighters who are in a fragile work situation,” Giardini explained.

The firefighters do not have permanent contracts, and they are understaffed in comparison with the areas they must serve. Each time a fire ignites, other groups of firefighters must be mobilized from other provinces to the affected areas.

Giardini emphasized the need for more investment in fire prevention and rapid-response infrastructure, in addition to stricter legislation to penalize intentional forest destruction. “On both a provincial and national level, prevention efforts [and] infrastructure for rapid fire response must be increased significantly,” Giardini said.

He suggested it is necessary for “the Congress of the nation to work on bills that have remained, in many cases, without progress [in terms of] penalizing the illegal destruction of forests, whether that is by converting them using deforestation or using fires. That would be another important tool to stop those who are trying to destroy the two forests illegally,” Giardini said.

Colombia: The risks of fighting the fire

Since the start of the year, in Colombia, high temperatures and the dry season have already caused fire threat alerts for 304 municipalities, mostly located in the Andean region. This is according to Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies in its Jan. 20 report. According to authorities, the country is experiencing weather with very few clouds and little rain, along with high temperatures and high levels of solar radiation. These factors have dried out the vegetation, converting it into potentially flammable material.

“Strong winds and previously deforested areas can make it so that, with dry, accumulated biomass, ready to be burned, the fire spreads rapidly,” said Rodrigo Botero, director of the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development. “As far as I know, there is not a single country in Latin America with a controlled burning system for the reduction of plant biomass,” Botero said.

According to Botero, the Colombia’s National Unit for Disaster Risk Management (UNGRD in Spanish) has shown that it has a good capacity to obtain and distribute information. Not only does the entity have a monitoring system for fires, but also for other natural risks. It is also connected to environmental institutions, territorial authorities and firefighting brigades from Colombia’s various departments and municipalities.

However, the country is facing an enormous problem when confronting larger fires. “The biggest Achilles’ heel is truly that it is still a very rudimentary [and] manual system, in which we depend on the support of the Air Force, which has some aircraft available for this purpose. This requires the development of a fire-control [aircraft] fleet that is robust, permanent and independent of the Armed Forces,” Botero said.

During the 2024 forest fire season, the Colombian government declared a situation of disaster and calamity, which “marked a critical point for Colombia, with a significant increase in the frequency and severity of these events due to high global temperatures,” the UNGRD said in a Jan. 17 statement.

They announced they were preparing to protect fundamental areas during 2025. In particular, there will be specific response plans for the national parks that are considered vulnerable, such as El Tuparro, Salamanca Island, Cinaruco, Sumapaz and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

However, Botero emphasized that Colombia is experiencing a particularly severe problem, distinct from other countries in the region: the presence of fires in areas dominated by armed groups, which threatens the integrity of entire teams of firefighters.

“This is a country in which fires and [figurative] minefields happen simultaneously. It is extremely serious; imagine the level of risk,” Botero said. “The matter is so serious that this issue has even been addressed in negotiations and meetings to include explicit protocols to stop the hostility against personnel who attend to natural disasters, including fires. I believe that this is an extremely important global precedent,” Botero added.

Botero also emphasized that, in Colombia, the crime of arson is minimized in the penal code. “There needs to be a legal categorization framework for fire management and for its classification as a crime in those cases in which premeditation, and intentional harm to natural resources and environmental services, have been proven,” Botero said.

Mexico: Fire management, a pending conversation

Records from the National Forestry Commission of Mexico indicate that, in Mexico, 2024 was one of the most devastating years for the environment. More than 1.6 million hectares (about 4 million acres) were consumed by the 8,002 fires recorded in the country’s 32 states.

According to the Mexican Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT in Spanish), in the last three years, Mexico has experienced a prolonged drought in addition to climate variation that has favored higher temperatures. The first few fires of 2025 are already occurring. In late January, 46 forest fires had been registered in seven states, destroying more than 522 hectares (1,290 acres), according to the National Meteorological Service.

Jardel, the Mexican fire management specialist, said Mexico, like many other countries around the world, has followed a policy of fire suppression, almost always reacting to the fires, mobilizing firefighters and investing in more technology, including machinery and aircraft.

Although Jardel said he believes there have been advancements in firefighting capabilities, he said conversations about fire management based on ecological principles are still pending in many areas of the country.

“This is a topic that remains relegated to the background of environmental and forestry policies, which themselves are always in the background,” Jardel said. “Although there have been times during which budgets have increased, the trend in the last few years is to reduce portions of the resources applied to these questions.”

Jardel added that “simultaneously, there is a greater transformation of the landscape, more people living in contact with forested areas and climate change, and what we have seen over the last six years is that the burned area has practically tripled in relation to the average of the 30 previous years.”

As larger areas tend to be affected by fires, Jardel suggested paying particularly close attention to forest management. Using ecological fire management techniques, effective fire prevention and control activities could be achieved.

“It is a social process and, of course, it involves a well-designed policy,” Jardel said. “We hope that in this [federal] administration, these issues are boosted and that they do not continue to be relegated to the background because, at the end of the day, [these issues] are depended upon for resources, for supplying water to cities and to agriculture and, of course, [for] the conservation of biodiversity, so it is a high-priority issue.”

Chile: Consequences for human life

In late January, there were 74 fires in Chile, of which 11 were still active, 29 contained and 34 extinguished, said Estefanía González, the deputy campaign director for Greenpeace Chile, in an interview with Mongabay Latam. Three private firefighters, working for the company Servicios Forestales Nacimiento, have lost their lives in the efforts to control the fires. Their deaths occurred in the Araucanía region on Sunday, Jan. 19.

“The situation has been pretty complex, especially in the central and south-central area of the country, which is the most affected now and also historically,” González said. “Some of the most complex fires are occurring in the Araucanía region in the Los Sauces commune, with more than 400 hectares [988 acres] burned, and in the metropolitan region, in the El Canelo area, with more than 100 hectares [247 acres] affected,” González added.

The fire season could last until April or May, so it is still early to take stock [of the situation], González said, which is why the focus should be on urban-rural interface zones and on any areas planted with pine and eucalyptus trees, which are highly combustible.

“We hope that the prevention efforts work, that there is a rapid response to the fires and that all the resources will be made available to fight the hotspots that arise,” González said.

Bolivia: In the heat of the emergency

Marlene Quintanilla, forest engineer and director of investigation and knowledge management for the Friends of Nature Foundation, said the fires in Bolivia burn in such an uncontrolled manner that each year is fiercer than the year prior. “The year 2024 was catastrophic,” she added.

“Ten million hectares [24.7 million acres] have burned, [and] a very significant portion [of the fires] have occurred in forests and in areas that, in prior years, we did not identify [as areas] that could burn; even the transitional zones of the Amazon have been destroyed by fire,” she said.

This situation even forced the Bolivian government to declare a “national disaster” in September 2024, aiming to channel international aid and the transfer of economic resources to the most-affected regions. These recent events act as an alert with respect to the year that has just begun, according to Quintanilla.

“There has been very slight progress in terms of planning how we are going to confront another year of fires; everything is in the heat of the emergency, and this is something that would be welcome to change in the country,” Quintanilla said. “Evidently, this year in particular has more challenges and the country’s economic context is also in a difficult condition and distinct from that of three years ago, when we had an economic condition in which resources could be allocated. This year is more economically complex for the country,” Quintanilla said.

Given the lack of resources, the best thing is to strengthen preventive measures. “From the political [side], we have to protect more ecosystems and more forests because those are what mitigate the effects of climate change,” Quintanilla said.

In addition, it is also urgent to strengthen regulatory frameworks and laws in order to sanction, in an exemplary way, fires caused by humans. “There are not really any exemplary sanctions to diminish this pressure,” Quintanilla said. For as long as this does not improve, she added, there will continue to be people who use fire to seize and clear land, with fires that burn not only in the place they intend to burn, but that will spread with the winds and temperature shifts caused by climate change.

“In Bolivia, we do not have the necessary preparation or the economy to attend to these mega-fires that have occurred with the previous management,” Quintanilla said. “Working on prevention would be the most important issue, and the regulatory framework is key to this.”