The wealthiest 1% of Americans now own more than the entire bottom 90% combined. That’s not a talking point — it’s a Federal Reserve data point. And the gap is still growing.

If you’ve ever felt like the economy is working really well for some people and barely working at all for everyone else, the numbers back you up. In the third quarter of 2025, the top 1% of U.S. households held 31.7% of all wealth in the country — the highest share since the Federal Reserve began tracking it in 1989.

Meanwhile, the bottom half of Americans held just 2.5%.

“An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics.”

These aren’t abstract statistics. They show up in everyday life: in the paycheck that doesn’t stretch far enough, in the medical bill that becomes a crisis, in the retirement fund that barely exists.

Let’s break down what’s happening, why, and what it means for regular people.

Who Owns What in America

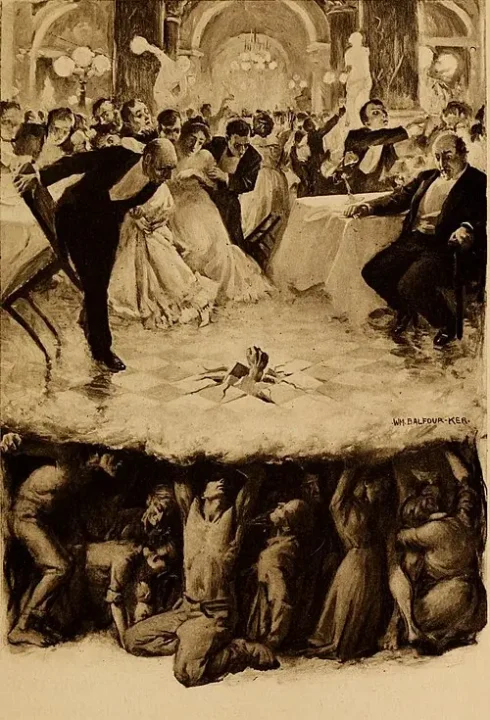

(William Balfour Ker)

Wealth — meaning everything you own minus everything you owe — is distributed in a way that would shock most people. The top 10% of households hold about two-thirds of all wealth in the country. The bottom half? They share roughly 2.5% of the pie among themselves.

To put that in real dollars: the top 10% of households held an average of $8.1 million each, while the bottom 50% averaged about $60,000. That’s not a gap — it’s a canyon.

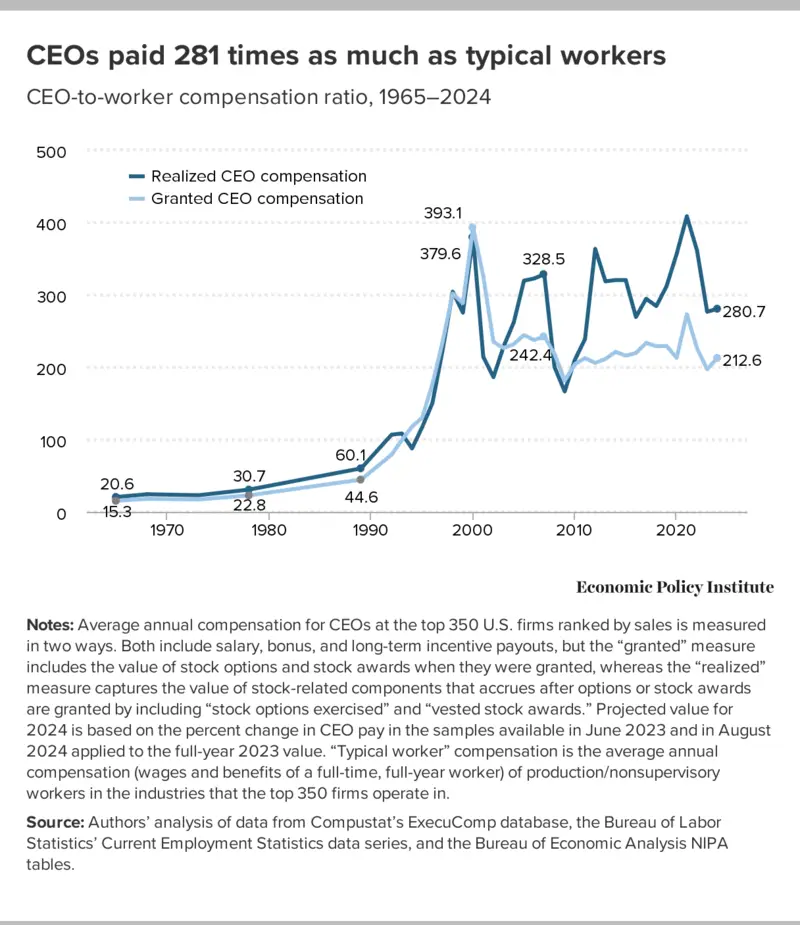

The CEO Pay Explosion

One of the clearest windows into how inequality has grown is the gap between what CEOs earn and what their employees take home. In 1965, the average CEO at a major U.S. company was paid about 21 times what a typical worker earned.

That ratio has since exploded. By 2024, CEO compensation at the 350 largest public companies had reached an average of nearly $23 million — roughly 281 times the pay of the average worker.

“We can either have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

CEO pay has risen more than 1,000% since 1978. Over that same period, the pay for a typical worker went up just 26%. That’s not a typo.

The people running the biggest companies saw their compensation multiply by more than ten times, while the people doing the work saw barely any movement at all — after adjusting for inflation.

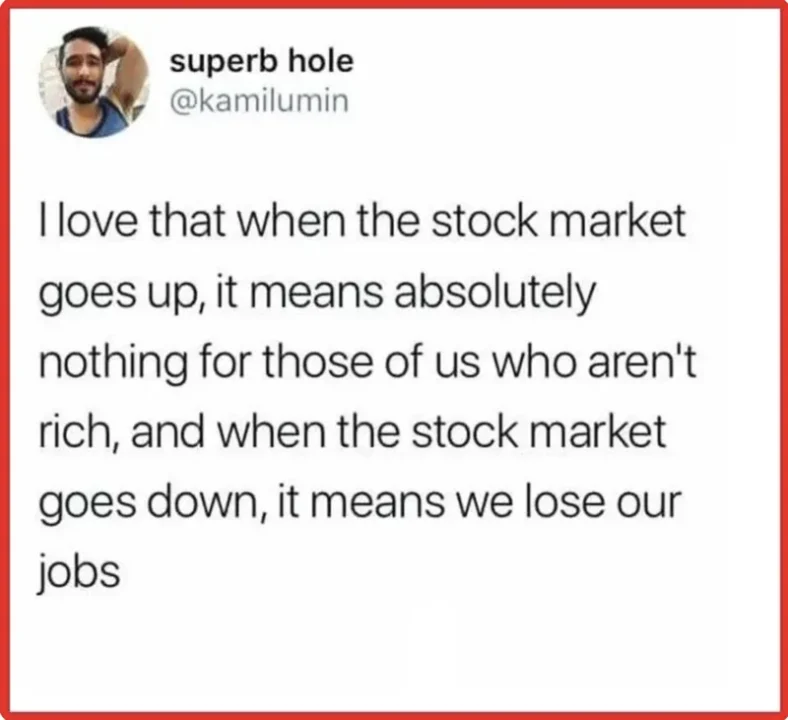

What’s driving this? In large part, stock-based compensation. About 79% of CEO pay in 2024 came from stock options and stock awards. When the stock market surges, executive pay surges with it.

Workers, on the other hand, are largely left out of those gains — only about half of Americans own any stock at all, and the vast majority of stock wealth is concentrated at the very top.

Why the Gap Keeps Widening

There’s no single cause. The growing divide is the result of several forces working together over decades. Wage stagnation is one of the biggest. Despite steady increases in worker productivity since the late 1970s, wages have barely budged. Workers are producing more value than ever, but they’re not seeing it in their paychecks.

Tax policy has also played a role. Corporate tax rates have dropped significantly over the past 40 years, and capital gains — the kind of income the wealthy rely on most — are taxed at lower rates than ordinary wages.

That means the higher you climb on the income ladder, the more favorable the tax code becomes.

The decline of labor unions is another factor. As union membership has fallen — from about 35% of private-sector workers in the 1950s to roughly 6% today — workers have lost bargaining power. Without collective pressure, there’s less to prevent the gains of a growing economy from flowing overwhelmingly to the top.

Then there’s the stock market itself. Wealthier households have a much larger share of their wealth in stocks and other investments. When markets rise, their wealth grows automatically.

Middle-class families, whose wealth is mostly tied up in their homes, don’t see the same benefit. And lower-income families, often carrying more debt than assets, can actually fall further behind.

In 1963, the wealthiest families had 36 times the wealth of middle-class families. By 2022, they had 71 times as much.

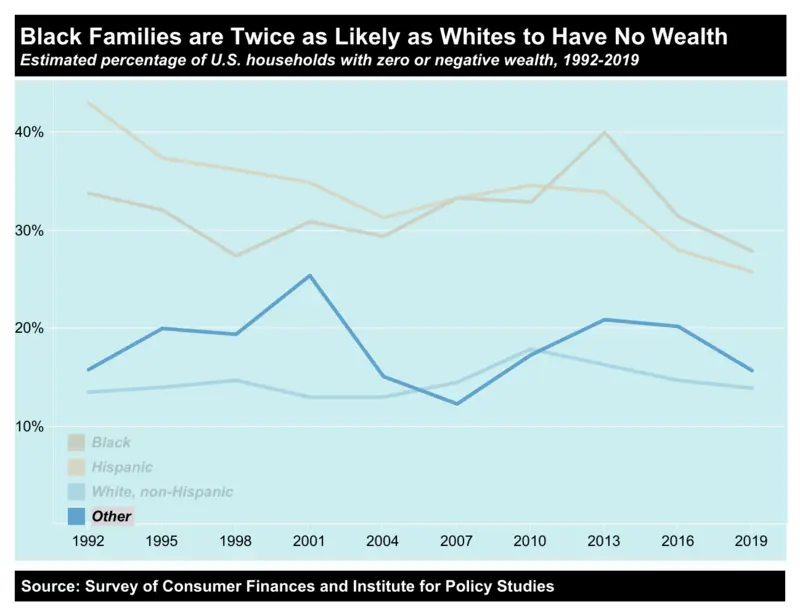

The Racial Wealth Gap Makes It Worse

Income and wealth inequality don’t hit everyone equally. White households held about 80% of all U.S. wealth in 2021, despite making up 65% of households. Black households, making up about 14% of the population, held just 4.7%.

The typical White household had roughly ten times the wealth of the typical Black household. Generations of discriminatory policies — from redlining to unequal access to education and lending — created a gap that continues to compound over time.

White families are nearly four times more likely to receive an inheritance, which further widens the divide.

What This Means for Everyday Americans

A growing wealth gap doesn’t just mean some people have nicer things. It shapes the quality of schools in your neighborhood, the healthcare you can access, the political power you can exercise, and the opportunities your children will have.

When wealth becomes this concentrated, it distorts democracy itself — because the people with the most money inevitably have the most influence over the policies that shape everyone’s lives.

This is why it’s so important that we get money out of politics.

Economists across the political spectrum agree that some degree of inequality is a natural part of a market economy. But the scale of what we’re seeing today — where CEO pay has grown more than 40 times faster than worker pay, where the top 1% holds more than the bottom 90% — goes well beyond what most people would consider fair or sustainable.

The solutions are debated, but the problem is not. The income and wealth gap in America is real, it’s growing, and it’s affecting the daily lives of hundreds of millions of people.

The question is: are we willing to do anything about it?