Watching the absolutely insane, cruel, and violent actions of what I call Trump’s “masked, militarized Special Police Force” in U.S. cities, I’ve often asked myself, are ICE Officials allowed to do that?

I can’t recall a time before President Donald Trump when ICE agents were breaking car windows to drag drivers out. Especially in cases where the person hadn’t even done anything wrong. If they were attempting to apprehend a violent criminal refusing to exit the vehicle, that’s one thing, but many of these victims have been innocent U.S. citizens.

ICE AGENTS BREAK A CAR WINDOW IN MASSACHUSETTS

I decided to do some research and look into what the actual policies and procedures are for ICE agents when dealing with the public. I should start by mentioning that it’s clear that they have some policies and rules of engagement—otherwise the Trump administration wouldn’t have pushed out ICE leadership and brought in Border Patrol following a statement where Trump said his masked secret police “aren’t going too far. They’re not going far enough.”

Because ICE deals with the public, they’re training is much different than Border and Customs Patrol who don’t come in contact with the public in their line of work. Instead, they’re accustomed to dealing with potentially dangerous people trying to enter the country illegally.

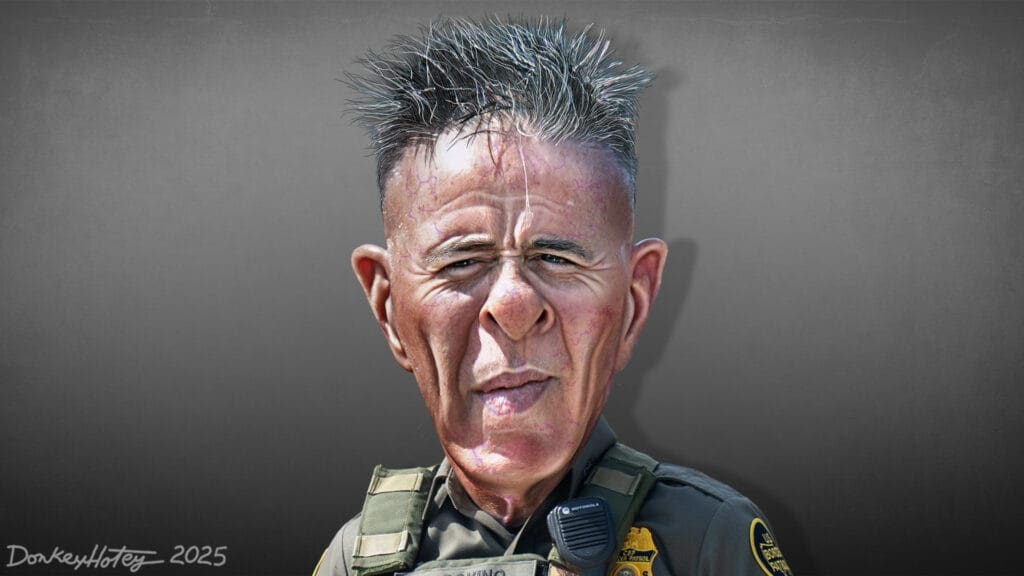

Greg Bovino has already gotten into trouble with the overuse of chemical agents against peaceful protesters (including children—the video of the 1-year-old being tear gassed was horrible ). CBP has also been involved in the shootings of two American citizens. Bovino was ordered by a judge to provide daily status reports on how things are going in Chicago (he has since had that ruling blocked on appeal).

NPR recently interviewed Nithya Nathan-Pineau, a policy attorney and strategist at the Immigrant Legal Resource Center to learn more about what ICE legally can and can’t do. The following are excerpts of the responses to NPR’s questions. If you wish to learn more, check out the full interview on the NPR website.

The Legality of ICE’s Actions

Q. Federal law gives immigration officials power to arrest and question immigrants. What are those powers? Can they make arrests without warrants?

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the agency in charge of immigration enforcement, was created after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Congress gave the burgeoning agency wide power to question, search and arrest immigrants, or those believed to be immigrants, without a warrant.

In the past, that has looked like investigative police work and arresting specific targets in specific locations, says Nithya Nathan-Pineau, a policy attorney and strategist at the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, a nonprofit that advocates for immigrants’ rights.

The Immigration and Nationality Act states that in order to arrest someone without a warrant, officers must have cause, or reasonable suspicion, to believe that a person is in the U.S. illegally and likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained.

“Leaving aside border checkpoints, immigration officers have power to consensually question anyone, just like a police officer does; but to detain soneone even briefly they require individualized suspicion that the person is violating the immigration laws,” UCLA’s Arulanantham says.

In the past, immigration officers would look for specific people who had, say, a final removal order issued against them or someone who was convicted of a crime – something that would render an individual deportable, Arulanantham says.

Now, in some cases immigration officers are executing major dragnets and arresting large groups of people and then determining if each person is in the U.S. illegally by interrogating them after they’ve been stopped.

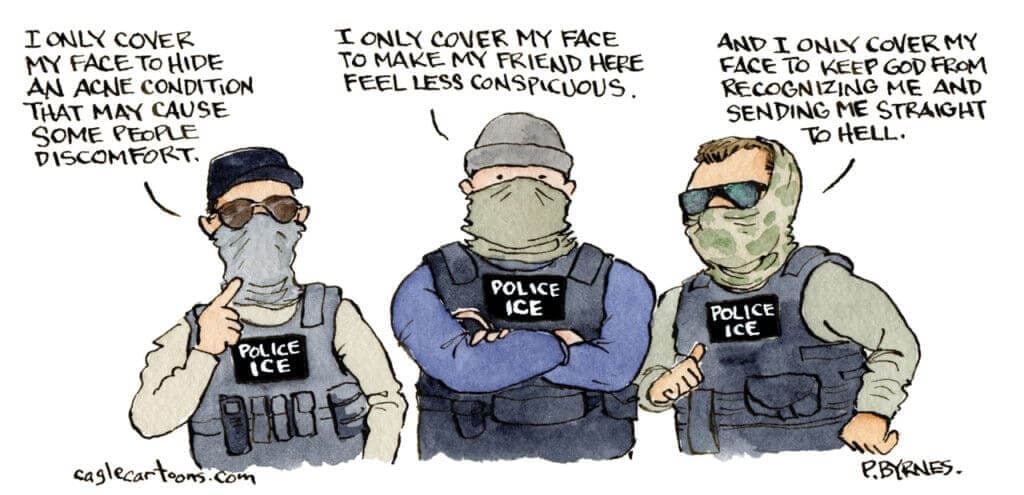

Q. Are immigration enforcement agents allowed to wear masks or otherwise refuse to identify themselves?

The widespread masking of immigration agents in the streets and even in federal courthouses has stoked fear among immigrant communities and strong objections from civil rights groups. But acting director of ICE, Todd Lyons, has said it’s a necessary response to what he describes as efforts to dox and threaten these agents and their families.

ICE has said there has been a dramatic increase in the doxing of agents but has not said how many cases there have been or provided any details. The agency has not provided any information to support their assertion of an increase in agent doxxing.

But Nathan-Pineau says this violates a federal requirement that immigration agents identify themselves as agents as soon as it is “practical” and “safe” to do so during an arrest.

(They are not, however, required to provide their personal names.) She says the regulation is interpreted as agents are allowed not to identify themselves during emergency situations where they have to work fast. But she says she doesn’t think the current situation constitutes an emergency that would justify agents not identifying what agency they work for.

Q. Where can officers make arrests? Can they arrest people in their home or a private business?

Immigration officers must have a warrant to arrest people at private businesses or homes. However, there are areas outside homes or in and around apartment buildings and businesses that can be considered public spaces. Immigration agents can, and have, made arrests in those types of areas, such as the lobby of an apartment building that’s open to the public or parking lots.

Private businesses have the right to decline entry to ICE.

However, ICE agents have used deceptive practices to gain entry into a person’s home or business to make arrests without a warrant, according to a lawsuit filed in 2020 against DHS. This has included ICE agents wearing vests that say “POLICE” and misrepresenting themselves as police or probation officers to trick people into allowing them into their homes or businesses. Four years later, a federal court ruled against this practice called ‘knock and talk,’ putting a stop to it.

Q. What are the rules on use of force?

Immigration agents are allowed by law to use force when they have “reasonable grounds to believe that such force is necessary,” according to DHS policy.

However, the law states an immigration officer should “always use the minimum non-deadly force necessary to accomplish the officer’s mission and shall escalate to a higher level of non-deadly force only when such higher level of force is warranted …”

And DHS policy encourages agents to use de-escalation techniques, less-lethal force and less-lethal devices, such as pepper spray and flashbang grenades, in achieving their goals. And they are to only use force that is “objectively reasonable.”

It’s unclear what the agency considers “objectively reasonable,” says Nathan-Pineau.