On October 28, 2017, an anonymous user appeared on 4chan, one of the internet’s most controversial message boards. Calling themselves “Q Clearance Patriot,” this person claimed to be a high-ranking government official with access to America’s most classified secrets. Their first post made a bold prediction: Hillary Clinton would soon be arrested, triggering massive civil unrest across the nation.

That arrest never happened. But the prediction sparked something far more consequential than anyone could have imagined—a conspiracy theory movement that would eventually reach millions of Americans and shake the foundations of our political system.

Birth of a Conspiracy Theory

The name “Q” referenced a real security clearance level used by the Department of Energy—one that grants access to information about nuclear weapons and materials. By choosing this name, the anonymous poster suggested they had insider knowledge at the highest levels of government.

Q’s posts, called “drops,” were deliberately cryptic and puzzle-like. They suggested that then-former President Donald Trump was secretly waging war against a hidden cabal of powerful elites. According to this theory, these elites were not just corrupt politicians—they were “Satan-worshipping pedophiles running a global child sex trafficking ring.”

The theory claimed that Democrats, Hollywood celebrities, and members of what believers call the “deep state” were all part of this evil network.

QAnon didn’t appear out of nowhere. It built upon an earlier conspiracy theory called “Pizzagate,” which falsely claimed that a Washington, D.C. pizza restaurant was the center of a child sex trafficking operation linked to Democratic politicians.

Conspiracy theorists claimed the pizzeria, Comet Ping Pong was the base of a child sex ring run by ex-US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and her aide, John Podesta.

When Edgar Maddison Welch showed up at the pizzeria in 2016 with an assault rifle, he told police he went there to “self-investigate” “pizzagate.” This demonstrated how online conspiracy theories could lead to real-world violence.

Meanwhile, the prominent theory propelling the QAnon movement into mainstream U.S. politics foretold real-world violence on an unprecedented scale.

QAnon supporters believed Trump, who was still in control of the U.S. Military, would order them to conduct mass arrests of thousands of Democratic politicians and conspirators during an event they called ‘The Storm.’

They believed mass public executions would be televised. This expectation became one of the movement’s most extreme and defining features.

EDITOR’S THOUGHTS: ‘The Storm’

There is one part of the QAnon movement that deserves serious reflection — and yet it is rarely discussed.

Central to the conspiracy was “The Storm,” a promised event in which Democratic politicians, journalists, and other public figures would be arrested and publicly executed for allegedly participating in a satanic child-trafficking ring. This was not a fringe detail. It was a core expectation.

What is difficult to ignore is how openly some people embraced this idea. Millions of Americans were not simply tolerating the prospect of mass executions — they were anticipating them. Some celebrated the thought of watching political opponents arrested and killed on live television.

Political disagreement is part of democracy. Anger at elected officials is common. But the normalization of mass political violence is something else entirely.

How did so many people come to see the execution of fellow Americans as justice — even entertainment? And what does that mean for a country built on constitutional rights and due process?

Even if individuals later abandoned the conspiracy theories, it is worth asking how a movement that openly fantasized about public executions gained such traction in the first place.

This is not about partisan politics. It is about the health of a democracy — and how easily calls for violence can become mainstream.

Beyond the apocalyptic promise of ‘The Storm,’ QAnon functioned like an online game blended with a political movement.

They adopted slogans like “Where we go one, we go all” (WWG1WGA) and believed that by decoding Q’s cryptic messages, they could predict the future.

Who Is Q?

The identity of Q remains a mystery, though researchers have developed theories. Evidence suggests the account may have started with one person—possibly a South African resident named Paul Furber who was a moderator on 4chan. Later, researchers believe Jim and Ron Watkins, who owned the message boards where Q posted, may have taken control of the account.

Three early followers—YouTuber Tracy Diaz and 4chan moderators Coleman Rogers and Paul Furber—played crucial roles in spreading QAnon beyond the dark corners of the internet. They created videos analyzing Q’s posts, built online communities on Reddit, and eventually turned QAnon into a business, selling merchandise and gaining followers.

From 4chan, Q moved to 8chan (later called 8kun), a site known for having almost no content moderation rules. From there, the movement spread to YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, where it found older, less internet-savvy audiences who took the theories seriously rather than viewing them as elaborate trolling.

Spread and Damage

Between October 2017 and June 2020, researchers at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) identified over 69 million tweets, 487,000 Facebook posts, and 281,000 Instagram posts mentioning QAnon-related content. What started as fringe internet “s**tposts” evolved into something far more dangerous.

QAnon has been linked to multiple acts of violence. In 2018, a follower blocked the Hoover Dam with an armored vehicle, demanding the release of government documents he believed would expose the “deep state.” In 2019, a man shot and killed a reputed Gambino crime boss in New York, believing the victim was part of the “deep state” conspiracy.

The FBI classified QAnon as a potential domestic terrorism threat in a 2019 “Intelligence Bulletin” memo, “This is the first FBI product examining the threat from conspiracy theory-driven domestic extremists and provides a baseline for future intelligence products. … The FBI assesses these conspiracy theories very likely will emerge, spread, and evolve in the modern information marketplace, occasionally driving both groups and individual extremists to carry out criminal or violent acts.”

Unclassified FBI Report

The movement also caused deep personal pain. Families were torn apart as loved ones became consumed by QAnon beliefs. People lost relationships with parents, children, siblings, and friends who descended into a world where they saw satanic conspiracies everywhere and trusted anonymous online posts over their own family members.

The Republican Party Connection

QAnon’s journey into mainstream Republican politics began in the summer of 2018. At a Trump rally in Tampa, Florida on July 31, 2018, QAnon followers made their first visible appearance, holding signs reading “We Are Q” and wearing shirts with large Q symbols.

Rather than distancing himself from the conspiracy theory, Trump amplified it. According to MediaMatters, before his Twitter account was suspended on January 8, 2021, Trump had retweeted QAnon accounts more than 315 times.

When asked about QAnon at a White House press briefing in August 2020, Trump said, “I heard that these are people that love our country” and noted “it is gaining in popularity.” He never condemned the movement’s dangerous beliefs about satanic pedophile cabals or its potential for violence.

By the 2020 election cycle, at least 86 congressional candidates had endorsed or given credence to QAnon theories. Two Republican candidates who won their primaries—Marjorie Taylor Greene in Georgia and Lauren Boebert in Colorado—had publicly supported QAnon beliefs. Greene called Q a “patriot” and said the theory was “something worth listening to.”

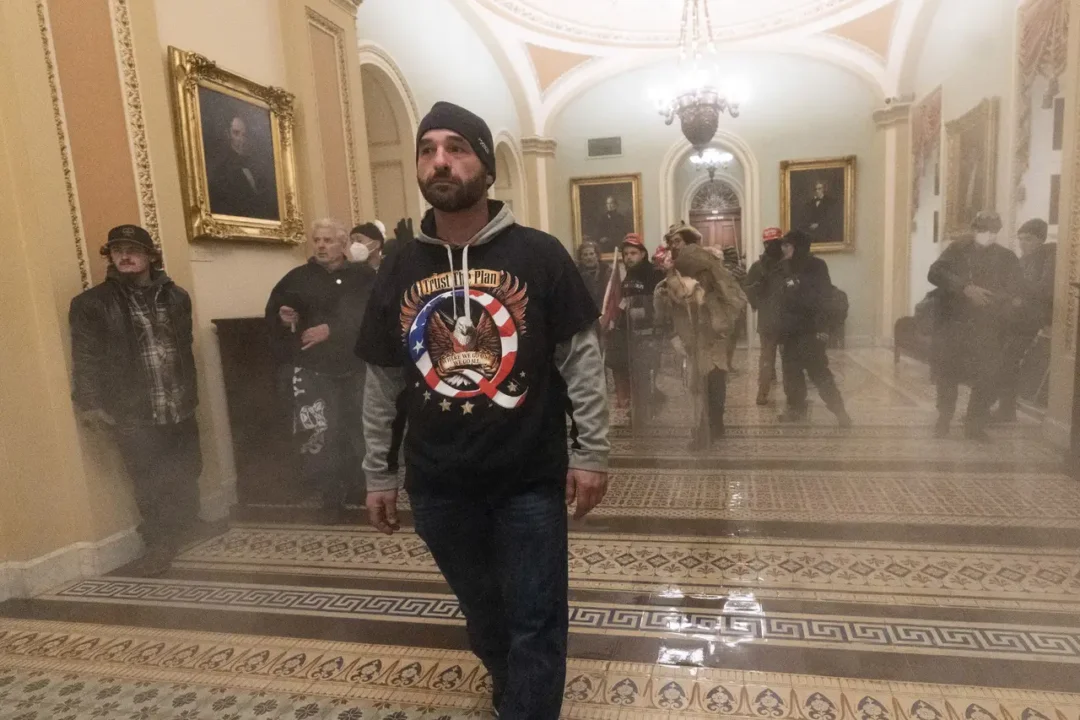

The movement reached its most violent peak on January 6, 2021, when a mob attacked the U.S. Capitol. Many rioters were QAnon believers who thought they were participating in “The Storm”—the long-promised day when Trump would finally defeat the “deep state.” One rioter, Douglas Jensen, wore a QAnon shirt and later told the FBI he put himself at the front of the mob because he “wanted Q to get the attention.”

Where Are They Now?

After January 6, major social media platforms cracked down on QAnon content. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube banned thousands of accounts and groups. Q stopped posting for a long time, returning only briefly in 2022 before going quiet again.

But QAnon didn’t disappear—it evolved and blended into mainstream politics.

Recent polling shows the movement’s beliefs have actually grown more widespread. A 2024 survey found that 19% of Americans now believe in QAnon’s core theories, up from 14% in 2021. Among Trump-supporting Republicans, that number reaches 32%.

The explicit QAnon branding has faded. Followers rarely use the term “QAnon” anymore, partly because Q himself advised against it, saying the mainstream media was using the name to discredit the movement. Instead, the beliefs have been absorbed into broader right-wing politics without the distinctive labels.

Trump’s continued flirtation with the movement has kept it alive. Since launching his Truth Social platform in 2022, Trump has shared over 130 posts from QAnon accounts, including images of himself wearing a Q lapel pin and posts featuring QAnon slogans. At rallies in 2022, Trump played music that QAnon followers embraced, and attendees made hand gestures associated with the movement.

When billionaire Elon Musk bought Twitter in 2022 and renamed it X, he allowed banned QAnon accounts to return. Both Musk and Trump have repeatedly shared QAnon content on social media. On the eve of the 2024 election, Musk shared a pro-Trump video where the word “patriots” appeared on screen with the O changing to a Q.

QAnon influencers have moved to less-moderated platforms like Telegram and Rumble, where they continue to build audiences and make money from their content. Some were even recruited to Trump’s Truth Social platform by Kash Patel, Trump’s pick to lead the FBI.

The ideas QAnon popularized—distrust of a “deep state,” anti-vaccine beliefs, and conspiracy theories about elite pedophile rings—have become commonplace talking points in Republican politics, even among people who would never identify as QAnon believers.

Researchers say this normalization is perhaps more dangerous than the original movement. As one expert put it, QAnon has “blended in” and its theories have been “diluted and normalized in a way that’s really insidious and effective.”

What started as an anonymous post on a fringe message board has become woven into the fabric of American politics. The explicit QAnon movement may have quieter branding today, but its influence on how millions of Americans understand politics, trust institutions, and view their fellow citizens remains powerful and deeply concerning.